It was a little after two in the morning. Picture this: I’m lying on the couch in complete darkness, phone in hand. The App Store is open, and I have been staring intently at that tiny blue “Get” button for an embarrassingly long amount of time. My heart is jumping around like crazy, and I’m about ten seconds away from starting to literally sweat. I feel guilty… although I’m not exactly sure why. My husband is asleep in our bed, and every few seconds I pop my head up to make sure I’m still the only one awake.

No, I wasn’t contemplating downloading a dating app and starting a clandestine affair. Well… technically it is a dating app, but I’m not interested in the affair. And for a few seconds after I download the app (an eternity, really), I am on a dating site for the first time ever. During that brief eternity, I find my mind going to some interesting (see: irrational, crazy, paranoid…) places:

What if I die right this moment and my husband finds this app on my phone and thinks I have this secret life!? What if my phone freezes before I get the chance to toggle over into BFF mode and then I have to explain why I have this dating app on my phone!? Oh My God, why did I do this!?

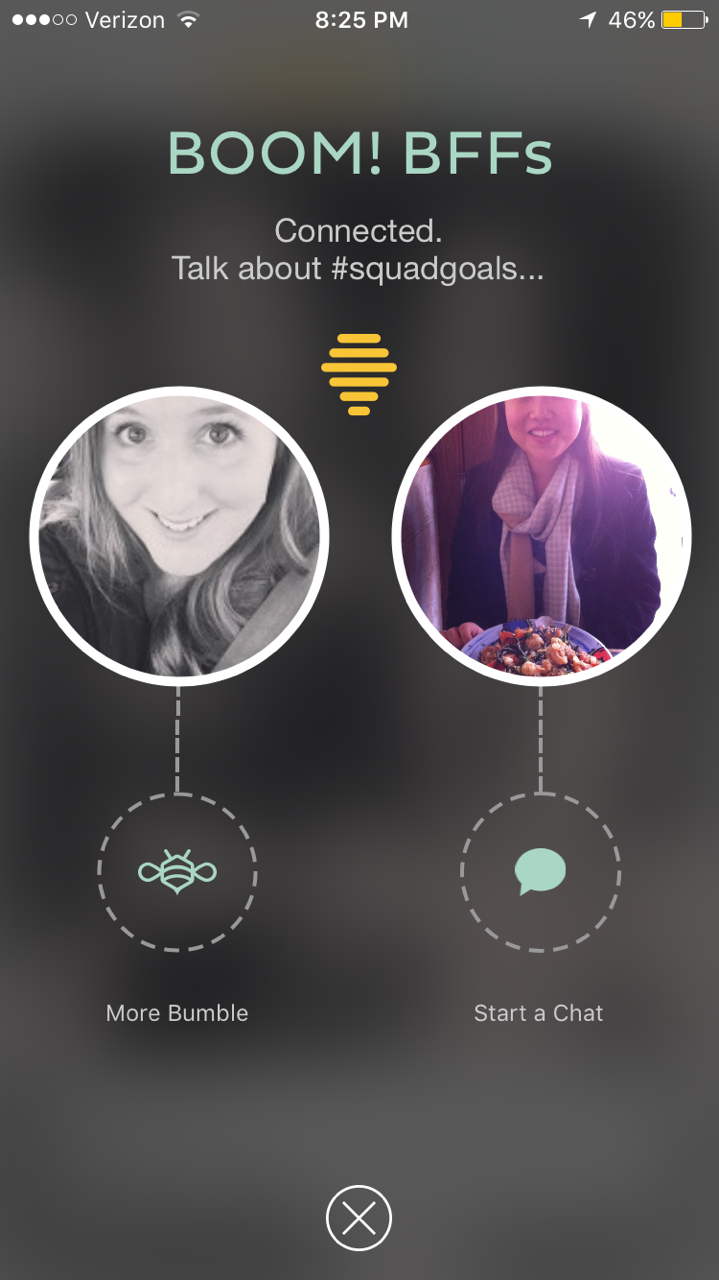

After I downloaded the app and switched to (the much safer) bff mode, the first step was to create a profile. Bumble bff prompts the user to import information from Facebook (there is a disclaimer that Bumble will never post anything to your account), and the app uploads your most recent Facebook pictures into your profile.

| Trying to avoid desperate vibes |

Here's mine:

The settings can also be adjusted to find friends within a certain distance from you (mine’s currently 20 miles) and friends of a certain age range (mine is set to find friends who are 24-34 years old). I originally had my distance set a little higher, but I kept getting Manhattan friends, so I adjusted. (Note: Manhattan girls looked a bit too intimidating).

The morning after I downloaded Bumble, I was alerted that I had my first match! Agh, so intimidating! What to say? Bumble acknowledges that making that first move can be intimidating as hell. They provide gifs:

Best one by far...

Oh, also,

there’s a taco:

I will admit, all the taco gifs in the world could not save me from feeling like I was on a job interview. At the start of any new convo, there was a lot of reaching for things to talk about-- too many “so what do you do?”’s, and “what did you go to school for”’s.

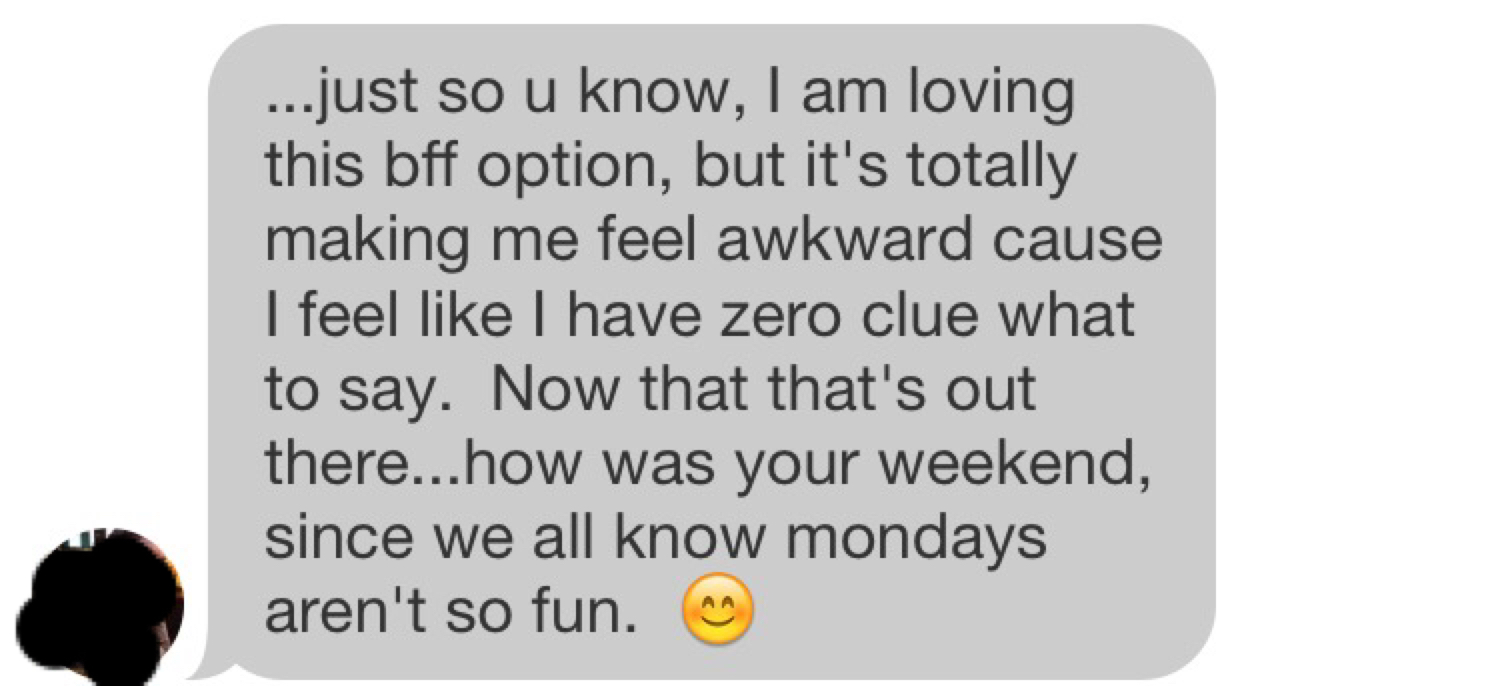

Some chose to acknowledge the awkwardness right away:

| Source |

But, ultimately, I saw the potential in the experience. After the awkward “getting to know you”, it was actually a little fun. Over the course of four weeks I talked coffee shops, school/work, vacations, kids, doughnuts, books, being friends with dogs on Instagram, and planning Pinterest-worthy parties with about 16 ladies.

As this media adventure comes to a close, I guess the big questions are: Was it worth it? And, did it work?

I set out on this adventure because of a few reasons. For one thing, I missed the whole dating app craze...but my best friend didn’t. She is a serial online dater and constantly talks about the connections that she makes online . I was never able to truly understand what the fuss was all about. Secondly, my online participation rarely goes beyond “liking” pictures and posts on Instagram and Facebook. And to be honest, most of that participation involves connecting with people that I already know--family and friends. I’ve never taken the opportunity to branch out and try to form new connections. This experiment was successful in provoing that exposure: it did give me insight into the online-connection experience, and I discovered what it feels like to really put yourself out there.

It was also validating to discover that someone that I might be interested in getting to know wanted to get to know me as well.

So, I would say that in this way, Bumblebff worked for me.. But did it lead to any new real friendships? Not yet. Do I expect it will? Honestly, not really.

Here is what didn’t work for me:

- You have to make split-second decisions about people based only on a few pictures and a short bio (bio’s aren't necessary, so some people didn’t even have one).

- Due to this lack of fluidity, the conversations and connections sometimes felt forced or unnatural. They never moved past the “small-talk” phase. It sometimes took days to get through the type of introductory conversation that would only take a few minutes if it occurred in-person.

- It was sometimes difficult to get a good read on people. I couldn’t really tell what kind of person someone was based only on the type of small-talk that we engaged in. I think that meeting people in-person allows for a better read on sense of humor, pet-peeves, and if someone is fun (or annoying) to be around.

With that said, I will likely keep the app on my phone and use it from time-to-time with the understanding that even though I don’t expect to find any new real-life best friends, it’s sometimes fun to talk to new people.

With that said, I will likely keep the app on my phone and use it from time-to-time with the understanding that even though I don’t expect to find any new real-life best friends, it’s sometimes fun to talk to new people.

I have had the same two best friends since the sixth (Jess) and eighth (Andrea) grade. I don’t think that the kind of relationship that we have can be replicated or grown from an online connection.

Here’s some unnecessary proof:

Real best friend conversation:

versus

Bumblebff convos:

To conclude: Bumble BFFs are people that you can make small-talk with when you’re bored; Real-life BFFs don’t do small-talk; there’s no need. Why talk about the weather when you can talk about how your bestie just matched with Black Phillip on Tinder.